The Ecma Natives Learning JS like a boss

Lab 2: Stay Classy

This lab is the second in a series of three labs where we don’t build anything awesome yet, but instead look at some of the fundamental building blocks of the language. Last week you did a lot of things with the different simple object types in JavaScript and next week we’ll cover some basic Test Driven Development (aka TDD). This week however we’re going to dive into “Classes”! We’ll also cover some functions, arrow-functions and simple objects.

Classes, functions and objects are among the basic building blocks for a lot of new (web) applications. Modern frameworks like Vue and React rely heavy on them, so this lab is going to among the most important labs so far!

Enough introduction let’s begin from the beginning.

What is a class

It’s good to know what this very particular tool in our tool-belt does before we start using it.

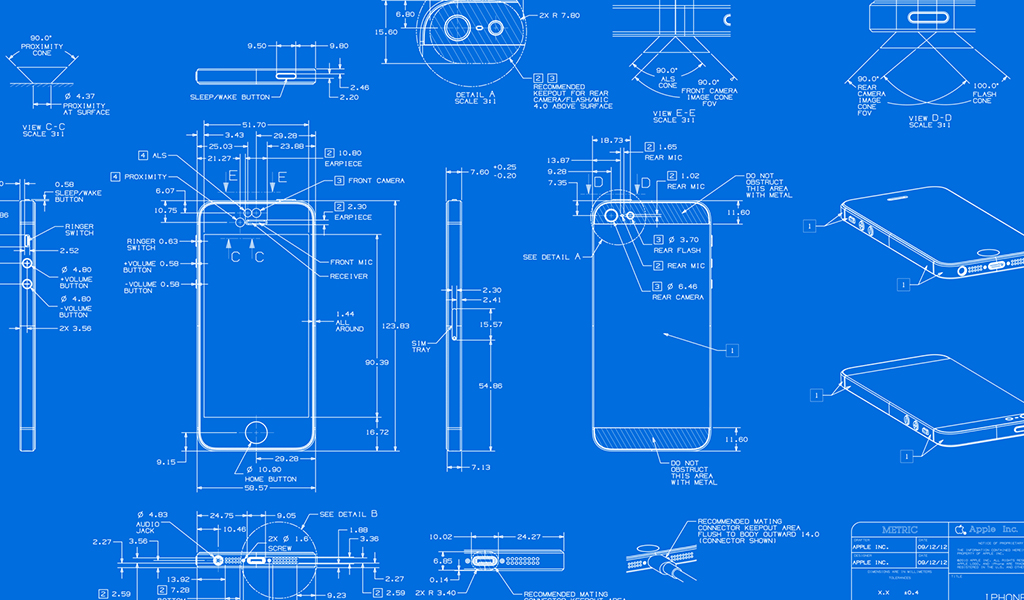

To explain classes I’m going to borrow the description Oracle gives on classes in their classes section on programming concepts.

In the real world, you’ll often find many individual objects all of the same kind. There may be thousands of bicycles in existence, all of the same make and model. Each bicycle was built from the same set of blueprints and therefore contains the same components. In object-oriented terms, we say that your bicycle is an instance of the class of objects known as bicycles. A class is the blueprint from which individual objects are created.

So the blueprint to a bike in JavaScript would look a bit like this (you don’t have to write this yet):

class Bike {

type;

colour;

wheelCount = 2;

speed = 0;

constructor(type, colour, wheelCount) {

this.type = type;

this.colour = colour;

this.wheelCount = wheelCount;

}

increaseSpeed(difference) {

this.speed += difference;

return this.speed;

}

decreaseSpeed(difference) {

this.speed -= difference;

return this.speed;

}

}

Just 2 wheels?

When we want to “build” a new instance of a bike we simply perform something among the lines of:

> bike = new Bike('mountainbike', 'red')

> bike.increaseSpeed(10)

10

Enough examples. You’re not here to just read.

starting a “real” project

Let’s start writing some code ourselves.

Until now you’ve written code in a single file, then executing that code.

We’re going to do things a bit different now.

When working with classes, components, modules and other patterns of programming it’s quite common to put different subjects in different files and call for them when needed.

So we’re going to “init” a project. Let’s begin at the beginning. Open a new terminal window on your machine. We’re going to assume that you have Nodenv with a working version of NodeJS installed (you did this in previous labs).

cd to the folder where you keep your projects & code snippets and create a new

folder like so:

$ mkdir classes_app

$ cd classes_app

In this folder we are going to “intialize” a new NodeJS project like this:

$ npm init

When you run that command it will ask you some questions. Fill them in like this:

package name: (classes_app)

version: (1.0.0) 0.0.1

description: ecma natives classes app

entry point: (index.js)

test command:

git repository:

keywords:

author:

license: (ISC)

Is this OK? (yes)

The values between ( and ) are default values. You only have to fill in

version and description, you can just hit [ENTER] on the rest of the

questions.

When done, try to execute ls -a to see the new file added to your project.

The package.json file that just popped up contains the basic information about

your project and its dependencies. We’ll open it up later. First we need take

care of some eslint grammar rules for our project.

ESLint introduces (code) grammar and spelling checks to our project

Execute the following command to install ESLint on your entire machine. We’ll need this in a bit to create a local configuration.

$ npm install -g eslint

$ nodenv rehash

The -g command tells the terminal to install a plugin globally on the machine

in the folder ~/.nodenv/versions/x/lib/node_modules. This way the plugin you

install will be available to the entire system. The plugin will however not

follow along when you share your project with others on sites like GitHub.

When you leave the -g out, the plugin will instead install in your project’s

package.json and its ../your-project/node_modules. But we’ll let the global

plugin take care of that in a bit.

The

nodenv rehashbit refreshes the list of commands that can be run using node. the Eslint installation added some commands to our terminal that we need.

The next step is the “project-only” installation of ESLint and the setup of the Grammar- and spelling-dialects we want to use (we call the combination of this grammar and spelling: “style-rules”).

$ eslint --init

ESLint will go through some questions with you. Use the Arrow keys on your keyboard to select the following options (in some cases you also need Space-bar):

? How would you like to use ESLint? (Use arrow keys)

(3) ❯ To check syntax, find problems, and enforce code style

? What type of modules does your project use?

(2) ❯ CommonJS (require/exports)

? Which framework does your project use?

(3) ❯ None of these

? Where does your code run?

◯ Browser (un-select with space-bar)

◉ Node (select with space-bar)

? How would you like to define a style for your project?

(1) ❯ Use a popular style guide

? Which style guide do you want to follow?

(1) ❯ Airbnb (https://github.com/airbnb/javascript)

? What format do you want your config file to be in?

(1) ❯ JavaScript

? Would you like to install them now with npm? Y (Type "Y" and hit ENTER)

Note: Some students (with custom typescript installations) have noticed an extra question in the list above. If you are asked if your project includes “Typescript” answer with “No”.

If you make a mistake, just hit <CTRL> + <C> on your keyboard and rerun

eslint --init

When you’re done, run ls -a. You’ll see four things in your project:

.eslintrc.js- A file with the ESLint “grammar dialect” (aka style-rules) we are going to use.node_modules/- A folder where all project plugins are installed.package-lock.json- A file specifying the locked versions of your dependencies.package.json- your project configuration.

Let’s open our project in Atom and load our package.json file (don’t forget

the ..):

$ atom .

It should look something like this:

{

"name": "classes_app",

"version": "0.0.1",

"description": "ecma natives classes app",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"test": "echo \"Error: no test specified\" && exit 1"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"devDependencies": {

"eslint": "^6.2.1",

"eslint-config-airbnb-base": "^14.0.0",

"eslint-plugin-import": "^2.18.2"

}

}

Let’s replace the test line to easily run an index.js-file later:

{

"name": "classes_app",

"version": "0.0.1",

"description": "ecma natives classes app",

"main": "index.js",

"scripts": {

"app": "node index.js"

},

"author": "",

"license": "ISC",

"devDependencies": {

"eslint": "^6.2.1",

"eslint-config-airbnb-base": "^14.0.0",

"eslint-plugin-import": "^2.18.2"

}

}

Good! Now that we are talking about an index.js file, we probably want to

create that file. Go back to your terminal and execute:

$ touch index.js

Open up the file in atom and write the following code:

console.log('test');

If everything in the editor is working as expected, you should be seeing the

following (when mouse/cursor-hovering over the console.log line):

Atom

Atom

sublime

sublime

Neat, our linter is telling us we are using code that should probably not be there when we release stuff to the internet later!

Check out the Atom and Sublime instructions in Lab 1 if you aren’t seeing grammar errors.

Congratulations, you have now probably spent 15 minutes on something entirely different than classes!

Let’s write a class

We create a new file in our project called book.js (you can do that in Atom

or use the touch book.js command like before in your terminal). This book.js

needs to sit in the same project folder as your package.json and index.js

In this book.js we’ll write the following code:

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = title.charAt(0); // first character of our title

}

}

module.exports = Book;

Let’s go over this code line by line:

class Book

Sets the name of our new class. Like a const a Class can’t be re-assigned to

something else. It’s probably good to mention regular naming of things in

javascript now:

- Classes always begin with uppercase and then CamelCase. A

mountain-bikeclass should therefore be namedMountainBike. Classes are also often singular as a new instance of a class often represents one object with properties and functions. - Normal variables begin with lower-case and continue CamelCase. So a regular

non-class mountain-bike would be named

mountainBike(the B is our camel’s hump). - File-names use underscores. So the file-name for the

MountainBikeclass should bemountain_bike.js.

constructor(title)

A constructor is one of the features that sets a class in JavaScript apart from

function objects. When you call new Book('Gardening'), JavaScript will

create a new “instance” – a unique new product from the class-blueprint –

and run the constructor first.

this.title = title

In our constructor we assign the title given when we created the class to the

this object. this is the current state of the object around that line of

code. In this case that is the new instance of our Book.

module.exports = Book

In module.exports we define what parts of the code are “exported” from our

JavaScript book.js file. These exported bits can be imported by other

JavaScript files. This is super nice as we can sort what variables in our

book.js file other files should have access to and what things should be private.

You normally assign either a single variable (Book in this case) or an {}

to module.exports

Importing and using a class

Now that we’ve written a simple book class it’s time to start using it!

Open up your index.js in Atom, remove all code you had in it (if there was

code in there) and write the following(ignoring the console linting warnings):

const Book = require('./book');

const book = new Book('gardening');

console.log('Book:', book);

console.log('title:', book.title);

const secondBook = new Book('cooking');

console.log('Second Book:', secondBook);

console.log('Second title:', secondBook.title);

Now instead of running node index.js, we run an easier command (one

that we set in our package.json earlier) like this:

$ npm run app

Book: Book { title: 'gardening', sorting: 'g' }

title: gardening

Second Book: Book { title: 'cooking', sorting: 'c' }

Second title: cooking

Now this is neat huh? Let’s go over the different lines of code we wrote!

const Book = require('./book')

In this first line we import the Book class we exported earlier and put it in

the variable Book.

new Book('gardening')

Here we create a new “instance” of a book where 'gardening' is the first

argument, gardening will be sent to the Book-constructor.

book.title

Since we have a new instance of a book we can ask for the objects assigned to its instance. The title being one of them.

Creating some functions in the class

We’ve created a class that can store some information for us. But classes can do a lot more! Let’s write some functions for our class. I’ll show you two methods of doing so.

Open book.js and make it look like this:

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = title.charAt(0); // first character of our title

}

logTitle() {

console.log('book:', this);

console.log(this.title);

}

logTitleAfter(seconds) {

const miliseconds = seconds * 1000;

setTimeout(this.logTitle, miliseconds);

}

}

module.exports = Book;

So here we create two functions:

logTitle()which willconsole.logthe title of our book.logTitleAfter()which will wait x seconds and then call thelogTitlefunction (spoiler: nope, this will fail)

Let’s call these new functions in our index.js (we’re commenting out our old

code with //, that way it won’t run):

const Book = require('./book');

// const book = new Book('gardening');

// console.log('Book:', book);

// console.log('title:', book.title);

// const secondBook = new Book('cooking');

// console.log('Second Book:', secondBook);

// console.log('Second title:', secondBook.title);

const book = new Book('gardening');

book.logTitle();

book.logTitleAfter(2);

And then execute it in our terminal:

$ npm run app

Hey something weird is happening!

Our call book.logTitle(); gave us what we wanted. It logged our book object

and then logged the title.

book: Book { title: 'gardening', sorting: 'g' }

gardening

But something went wrong with the time-out… All of a sudden the this object

isn’t our book anymore, but a timeout object.

book: Timeout {

_idleTimeout: 2000,

_idlePrev: null,

_idleNext: null,

_idleStart: 30,

_onTimeout: [Function: logTitle],

_timerArgs: undefined,

_repeat: null,

_destroyed: false,

[Symbol(refed)]: true,

[Symbol(asyncId)]: 6,

[Symbol(triggerId)]: 1

}

undefined

So we have switched contexts somehow when the function was used in a “callback”. To get the book back we can attempt two things.

In older versions of Javascript (up till ECMAScript 3) we’d need to bind stuff like:

setTimeout(this.logTitle.bind(this), miliseconds);

Or create an anonymous (lambda in Python) function (looks messy):

const that = this;

setTimeout(function() {

that.logTitle();

}, miliseconds);

In ECMAScript 2015 we got access to so called arrow-functions. These

arrow-functions respect the this context around the caller a bit better. Right

now TC-39 is working on getting those arrow functions for classes working in

the newest version of ECMAScript. Let’s rewrite our book.js a bit until it

looks like this:

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = title.charAt(0); // first character of our title

}

// the line below will raise a linter error. that's fine.

logTitle = () => {

console.log('book:', this);

console.log(this.title);

};

logTitleAfter(seconds) {

const miliseconds = seconds * 1000;

setTimeout(this.logTitle, miliseconds);

}

}

module.exports = Book;

using arrow-functions as class-functions is extremely new. TC-39 is currently working on making browsers & platforms work with it under the ES7 specifications. Your linter is still tuned to ES6, the line will work fine on the terminal. Using normal arrow functions is fine though.

$ npm run app

book: Book {

logTitle: [Function: logTitle],

title: 'gardening',

sorting: 'g'

}

gardening

book: Book {

logTitle: [Function: logTitle],

title: 'gardening',

sorting: 'g'

}

gardening

Well, the result from that looks much better!

You could also choose to write the class like this (and create code that is compatible with ES 2017):

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = title.charAt(0); // first character of our title

}

logTitle() {

console.log('book:', this);

console.log(this.title);

}

logTitleAfter(seconds) {

const miliseconds = seconds * 1000;

setTimeout(() => {

this.logTitle();

}, miliseconds);

}

}

module.exports = Book;

A note about compatibility

Should you write code that is compatible or shouldn’t you? This is of course a pretty good question. In most cases where we write code for the web, apps or other front-end platforms compatibility matters!

But on the other hand, One of the projects that I worked on had 100 or so JavaScript files. It would have been horrible if a visitor to that website had to download 100 different files. It’s much easier to just download one file.Normally we use an engine to bundle those files together like Webpack, Grunt, react-native, etc. Most of these engines can be configured to use Babel A translator that turns new fancy code into old code that can be used by older browsers. So no worries!

Static functions

So far you’ve been instantiating new instances of your book class with

new Book(). In that “Instance” of our class we had some variables and some

functions. Let’s open our book.js and add an extra function:

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = title.charAt(0); // first character of our title

}

logTitle() {

console.log('book:', this);

console.log(this.title);

}

logTitleAfter(seconds) {

const miliseconds = seconds * 1000;

setTimeout(() => {

this.logTitle();

}, miliseconds);

}

static favorites() {

return [new Book('Gardening'), new Book('Cooking'), new Book('Fishing')];

}

}

module.exports = Book;

And in our index.js we’ll do this:

const Book = require('./book');

// const book = new Book('gardening');

// console.log('Book:', book);

// console.log('title:', book.title);

// const secondBook = new Book('cooking');

// console.log('Second Book:', secondBook);

// console.log('Second title:', secondBook.title);

// const book = new Book('gardening');

// book.logTitle();

// book.logTitleAfter(2);

console.log(Book.favorites());

And then let’s run that function:

$ npm run app

WOW, so even though we had a function in our class, we could run it without

having to do new Book() first. So these functions and variables are quite

awesome if you want your class to have some extra tools (like mass-creation) you

can use statics.

Arrow functions?

In the examples above we’ve been trying out some fancy new Arrow Functions. Let’s play with them a bit more.

Create a new file called tools.js in the same folder as index.js and

book.js. You can create the new file in Atom, or write touch tools.js in

your terminal.

The purpose of our tools file is to create some crafty little tools to make our book code work a bit better.

In the new tools.js add the following code:

const timer = {

seconds: (seconds) => seconds / 1000,

Minutes: (minutes) => this.seconds(minutes / 60),

};

const sortLetter = (word) => word.charAt(0).toUpperCase();

module.exports = { timer, sortLetter };

There are a lot of things happening in this file. Let’s go over them:

The timer

The timer will turn seconds or minutes into milliseconds (the default format for

setTimeout, cookies and a lot of other time-related things in JavaScript). Since

our timer only exists out of statics, there is no reason to make an entire class

for it. Instead we create a small simple object for it.

(seconds) => seconds / 1000

So this is an arrow function where { return seconds / 1000 } is simply noted

as => seconds / 1000. If an arrow function has no {} and only one line of

code, the result of that one line will be returned.

module.exports = {timer, sortLetter}

So here we create a new object that looks like this

{ timer: timer, sortLetter: sortLetter}, but because both the keys and values

have the same name, ES 2015 prefers us to just write the name once.

The module exports is an {} object in this case.

Let’s import it on our book.js file and do some fun things with it.

const { timer, sortLetter } = require('./tools');

class Book {

constructor(title) {

this.title = title;

this.sorting = sortLetter(title);

}

logTitle() {

console.log('book:', this);

console.log(this.title);

}

logTitleAfter(seconds) {

const miliseconds = timer.seconds(seconds);

setTimeout(() => {

this.logTitle();

}, miliseconds);

}

static favorites() {

return [new Book('Gardening'), new Book('Cooking'), new Book('Fishing')];

}

}

module.exports = Book;

The only big weird thing we do here is

const { timer, sortLetter } = require(('./tools')). This is a new way of

creating new variables from an {}. In old ECMAScript 3 we would need to have

written something like this:

var tools = require('./tools');

var timer = tools.timer;

var sortLetter = tools.sortLetter;

That’s a lot of code right? so ECMAScript 2015 came with the neat functinality to do things like this:

const { foo, bar } = {foo: 'hello', bar: 'baz', zed: 'hey'};

console.log(foo);

console.log(bar);

Much easier and you can use the variables straight away!

Let’s continue and update our index.js to make everything functional again

We’ll remove the // things. Your linter will tell you that you are defining

const book twice. You can remove the second instance:

const Book = require('./book');

const book = new Book('gardening');

console.log('Book:', book);

console.log('title:', book.title);

const secondBook = new Book('cooking');

console.log('Second Book:', secondBook);

console.log('Second title:', secondBook.title);

book.logTitle();

book.logTitleAfter(2);

console.log(Book.favorites());

cheat: select the text that is commented out and hit

[CTRL]+[/]to toggle commenting on that code!

$ npm run app

Boom code works!

Let’s recap

You’ve done a lot today, let’s sum it up:

- You created a new project using

npm initand installedeslintto it to get awesome style-checking on your code - You imported a class defined in

book.jsinto your main fileindex.jsand you imported a toolbox of handy things from an object into yourbook.js. - You created a class blueprint and made instances of that class. Then you added static functions to that class to mass-create instances in a list.

- You commented and uncommented some code.

- You played around with new JavaScript ways to create objects

(

{timer, sortLetter}) and you assigned 2 items from an object in a fast way. - I hope you had lots of fun!

Next week we dive into Test Driven Development. A way to write code that tests

itself for errors!

See you next week!